I think a lot about how we as human beings are connected, tethered, and obligated to other human beings. If you’ve read my other blog posts or have ever had a single conversation with me, this has probably become apparent. maybe it’s my sociological training or maybe it’s the years spent playing a balancing act with my family’s precarious dynamics as the peacekeeping oldest sister.

the concept is especially interesting to me in a country that runs on an almost paradoxical notion of self and society. I am far from the first to say this, but I’ll say it again: in the united states, we often find ourselves motivated by a self-preserving and self-sabotaging individualism. it’s what colors the discourse of our politics, the way we raise our kids, and the things we spend our money on. it’s what’s led to the feeling of chronic loneliness and disconnection that we see throughout the nation.

and yet, on the other side of the coin, we are a society with a capitalist system that survives on a sort of self-sacrificial puritanism; we are quick to give ourselves up—our identities, our bodies, our time—for the sake of others. american friendships are characterized by our fake niceness and superficial friendships, it’s considered standard for employees to over-exert themselves in their jobs at companies that never really offer personal reward, and we sell ourselves as brands on our own social media accounts for the consumption of others. nearly everything we do is for the sake of the people and systems around us.

it becomes interesting, especially, when the groups and communities we place ourselves in become wrapped up in our notions of identity. when the group is what defines how we see ourselves. a sociologist by the name of goffman came up with a concept known as a ‘total institution.’ it describes “a place of work and residence where a great number of similarly situated people, cut off from the wider community for a considerable time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life.” these total institutions often require that we need to resocialize ourselves in order to understand how to work and behave within the social structure of that specific institution. common examples of a total institution are a police force, the military, prison, or a college campus. in these places, the rules and expectations are different from the outside world. when we find ourselves in these total institutions, it reshapes the way we view our relationships with other people. we see them as the role they fulfill—professors, servers, managers, frat boy—rather than as individuals. ever run into a teacher or professor at the grocery store outside of school and you’re completely thrown off because you don’t know how to interact with them as a real human being?

but the scary part is when, within these total institutions, we begin to lose our own sense of self. we begin to lose our ability to distinguish between ourselves and the environment we have encased ourselves within. convincing yourself into believing the delusion that if you sacrifice yourself for the good of the company, you’ll somehow receive some benefits for yourself. this way of thinking, I think, makes our relationships and our interactions feel less meaningful. you’re no longer creating a relationship with someone as a human being, but to fulfill a utilized purpose.

as someone who has had a bad habit of getting too emotionally involved in codependent relationships—with partners, with siblings, with organizations—I know what it feels like to have your actions and choices no longer feel like yours. to no longer recognize the person you’ve become and only be able to see yourself as a product of your environment. to only know an identity through how you are perceived by others.

and so, what happens when an overachieving, over involved, former-student-body-vice-president-turned-valedictorian graduates college and is suddenly taken out of one of the most all-encompassing, life-sucking total institutions of her life? well, she runs away, flees the country, and has an identity crisis.

and let me tell you, this whole being alone thing? terrifying.

imagine showing up to a hostel in the middle of the night after braving the dark and rainy alleyways. you’ve spent the evening on unfamiliar streets dodging overly excited motorbike drivers who are calling out to you in a language you can’t quite understand enough to decipher whether the phrases are catcalls, insults, or taxi ride offers. the receptionist at the front desk hands you a stack of questionable-looking towels and leads you up to your mosquito-infested room with six other slumbering strangers. you do your nightly skincare routine at the shared sink and try your best to not look at the oddly-colored stretch of what looks like mold growing across the ceiling while you apply your retinol. then, just as you’ve finally gotten settled in your bed—the bottom bunk closest to the door, nonetheless—and you draw the curtain closed, you hear the door open. a group of loud, drunk, belligerent men stumble into the room (as someone who has keeps to their skincare routine like a religion and has an unresolved fear of men, this was a nightmare scenario)

you’re alone. no one knows you. all of your emergency contacts and trusted confidants are on an entirely different continent in an entirely different time zone. the only person who knows your name is the sleepy receptionist. if you were to disappear the next day, there’s not going to be a search team desperately looking for you. you’re a solo traveler.

another aspect of community that I think we are often overlook is its ability to offer a sense of security and safety. when the community is small enough that almost everyone knows everyone, word gets around quick. complete anonymity is almost impossible. membership to the community almost feels like an extra layer of insurance. there’s the assumption that you are less likely to be harmed if you have an entire community looking out for you (this may be a delusion when you take into account statistics like the fact most instances of rape on college campuses take place between individuals who know one another. but, I digress.) the reason we think this way, however, is that in this community—in this institution—we have the power of social pressure.

foucault is a french philosopher who has a lot of writings on policing and what he calls “biopower”—power over life. the power to control one’s behaviors and actions through coercion, persuasion, or surveillance. and when we think about biopower, what often comes to mind are stronger, more explicit institutions, such as the government or the police. but, in order for those to function, we all need to be willing participants. within a community, we all have biopower.

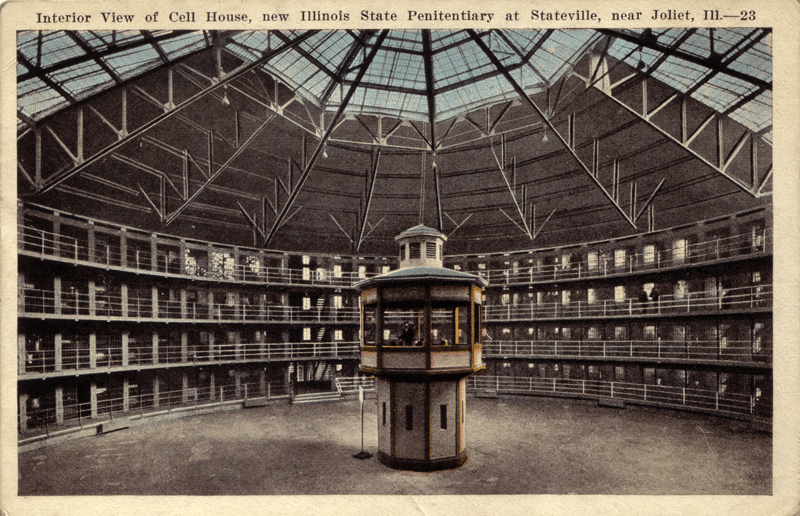

he talks about this using a metaphor for a specific design for a prison: the panopticon. imagine a circular prison with prison cells all around the circumference of the circle. there are multiple floors so, past the solid brick wall on top of you, below you, to your right, and to your left, there are other prisoners in other cells. but, on the wall facing the inside of the circle, the prison cells have bars that can be seen through. from your vantage point, you can see into the cell of almost every other prisoner, and they can see into yours. in the middle of the prison, there’s a large tower. it’s a watchtower with prison guards watching from the very top. just as you can see into every other prison cell, they can, too. but there are too many cells for the prison guard to watch every single prisoner at once; only god can be omnipresent. the room at the top of the watch tower, however, has a bright light. a light so bright that you can’t see even see into the room at the top of the watch tower. so, while you’re sitting in your cell, you can’t tell whether or not the prison guard is watching you. you can never find a moment where you are absolutely sure that you’re not being watched so you can’t carry out your plan to escape. so you simply behave as though you are being watched, all the time.

but here’s the catch, none of the other prisoners want to be reprimanded either. and human beings have funny habit of getting upset when they witness unfair treatment—like watching someone getting away with something that you weren’t able to. and, remember, every other prisoner can see into your cell and you can see into theirs. so when you catch a prisoner on the other side of prison trying to pick the lock and escape, you call out to the prison guard in the watch tower and tattle so that the other prisoner can get punished. and so, unwittingly, every prisoner in the panopticon becomes a watch guard for everyone else. the guard does not have to even be watching in order to impart social control. hell, he doesn’t even need to be sitting in the watch tower. we have all already become implicated in the very surveillance that keeps us confined. we behave and we keep one another in check, at our own expense.

the panopticon is in every aspect of our lives, whether we are part of a smaller community or not. it’s in the surveillance cameras at the traffic lights catching you run the red light, it’s in the social media apps mining endless amounts of data about our lives, it’s in the gossip that we tell our friends. i’m not saying that the panopticon is necessarily always a bad thing. in fact, in our world where the internet has overloaded us with information and desensitized us to violence, I think it’s often necessary that we keep one another in check.

but, imagine, if just for a moment, you were released from that panopticon. if you were able to run away to a new country where no one knew you. where no one belonged to you and you belonged to no one else. you’re on your own, your stay is temporary, and you can create the identity you’ve always wanted to without fear of recourse.

it was liberating. like letting go of a breath I didn’t even realize I was holding. like finally getting a chance to see myself outside of responsibility, obligation, or reputation.

it gives you the room to mess up; to make a fool of yourself at a cafe because you don’t know how to ask the barista where the restroom is so the two of you are left making some obscene hand gestures in a public game of charades. it makes you feel more willing to take risks: wear clothes you would never wear at home, go out to the bars without makeup or deodorant after a long day of hiking, read poetry at an open mic, sing at a jazz club, dance in public. it was like being a little kid again.

now don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I just became a completely different person. but for the first time in years, escape from the watchful eyes of everyday life was like an opportunity to try out different parts of my personality. to become more sure of myself and the parts of me were really me. being alone made me more attuned to my preferences, my tendencies, my limitations, and my sources of joy. all of these, I could determine on my own accord without having to be considerate of someone else’s feelings.

one of the most surprisingly delightful parts of being alone were my interactions with the people I met. whether it be the silly interactions I had with my hostel bunkmate, the eye-opening conversations I slipped into with locals, the enthralling stories discussed over vietnamese iced coffee, or the adventures I went on with friends from the homestay, these interactions were all loving and beautiful for their own sake. there were no social repercussions for being shitty, but there were also no social rewards for being genuinely good.

throughout every interaction, there was an underlying sense of detachment: there was little intention of community-building and it’s unlikely that I’ll ever see many of these people ever again in my life. but the temporality of it all—the fact that there were no expectations of building a longterm relationship—made the kindness almost feel warmer. I was receiving the generosity of these people simply for the sake of it. altruism simply because we wanted to share these brief memories with one another. it’s made me excited to return home with a newfound sense of joy for my friendships.

traveling alone has taught me quite a bit. about myself, my culture, and the world. at the core of it all, this experience has taught me to have more trust. trust in myself and my abilities; I now know I have the wit and will to get out of even the stickiest of situations. trust in the world; realizing that there are more good people than there are bad people (so living a life of suspicion and paranoia will only reduce your chances of interacting with the good people who want to help you). trust that I can find good experiences wherever I go, even if things don’t go according to plan. and trust that if I meet the universe with generosity, it will return with the same.

I’m back home in the states now. it’s a completely different context than the one I was in the last time I was here. I’ve graduated school, I’m living out in the city, and I’m on the hunt for a big girl job. it’s too early to tell what new type of panopticon or total institution I’ll inevitably find myself entangled in. but, for the first time in a long time, I’m not worried about my future. I have a better idea of the person that I am; the identity that feels most comfortable on me outside of the social pressures of society. all of a sudden, the adult world isn’t so scary anymore. if I could survive the mosquitoes, waterfalls, and motorbikes of southeast asia, I can conquer whatever life has in store for me next. trust me.